Patellar instability describes the kneecap sliding out of the joint either completely (dislocation) or partially (subluxation). It is a common source of knee problems and is much more common in people under the age of thirty. In fact, patellar instability is rare in people older than 40 years of age.

Anatomy – Knee and Patella

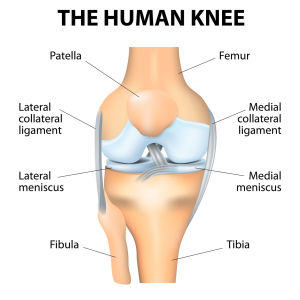

The knee is composed of three bones:

- Thighbone (Femur)

- Shinbone (Tibia)

- Kneecap (Patella)

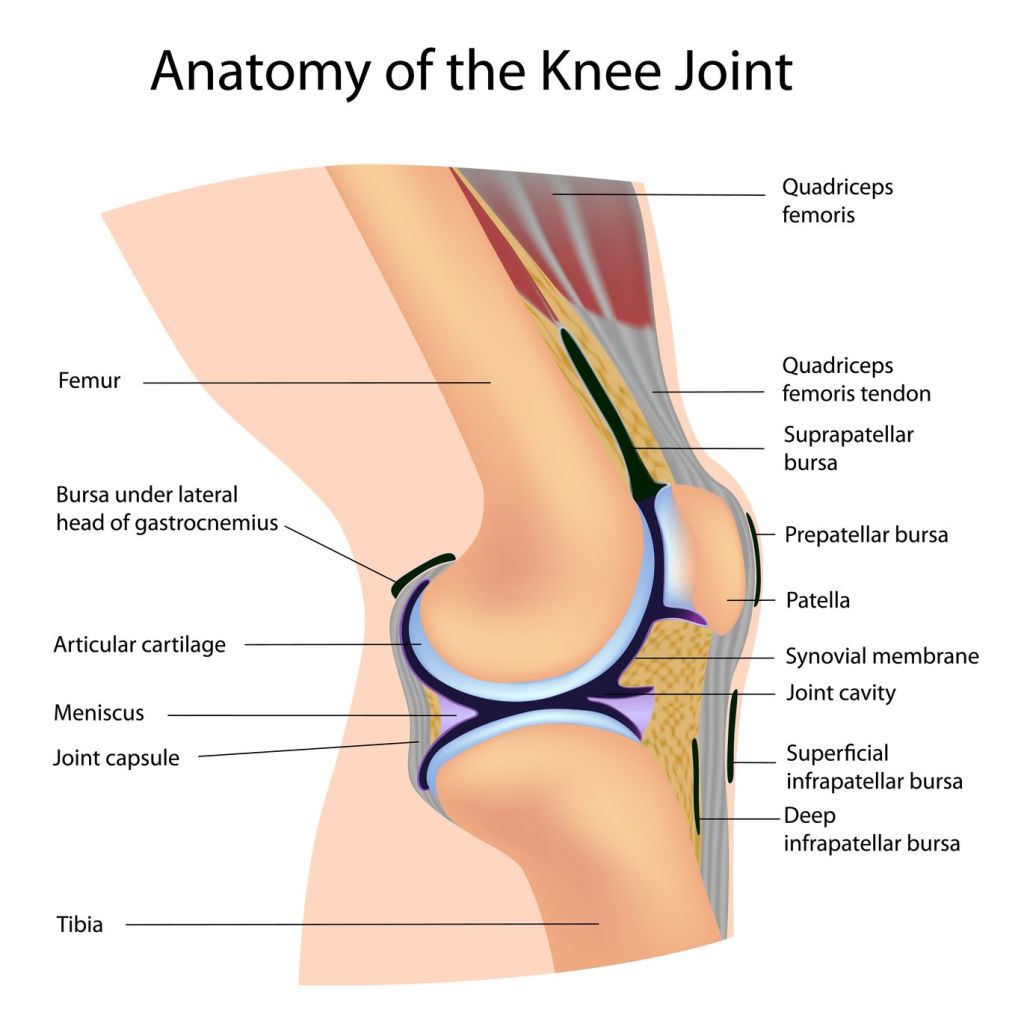

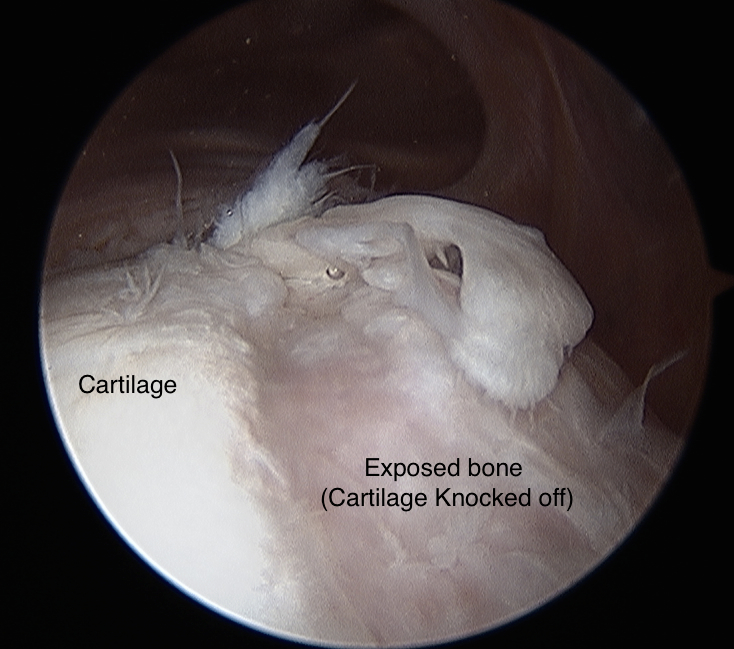

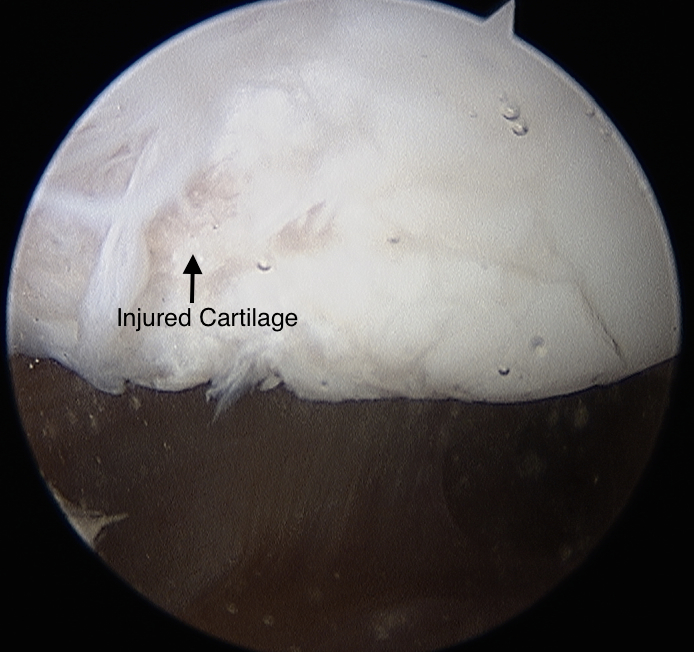

Each bone, when healthy, has cartilage on its surface. Cartilage is that smooth glistening substance seen on the end of a chicken bone. It has no nerve fibers and is one of the smoothest surfaces that exists. It caps and protects the ends of the bones.

The bones are held together by ligaments that connect them directly to one another, the capsule, which is the lining of the joint and muscles that cross the knee and move the bones with their tendon attachments.

The patella normally rests in a groove on the front of the femur. This groove is called the Trochlear or Femoral Groove. The V-shape of this groove usually matches the shape of the patellar undersurface and by doing so provides some stability to the kneecap joint.

The kneecap sits within a tendon that runs from the quadriceps muscle of the anterior thigh to the front of the upper shinbone. The patella is also connected and stabilized by ligaments on its inner side (Medial Patellofemoral Ligament or MPFL) and thickening of the capsule on both its inner and outer sides (Medial and Lateral Retinaculum, respectively).

Although there is normally some play in the kneecap’s motion, it usually remains within the trochlear groove as the knee bends (flexes).

The kneecap’s primary function is to increase the straightening (extension) strength of the knee and to protect the front of the knee.

Anatomy – Patellar Instability

When patellar instability occurs, two injuries to the structures of the knee commonly result. Typically the kneecap slides out of the trochlear groove to the outside of the knee, away from the opposite leg. When this happens, an injury to the MPFL inevitably occurs. This ligament may pull off the inner border of the patella or from its attachment on the end of the thigh bone or it may stretch and potentially tear within it’s mid substance. This tearing may also extend into the nearby retinaculum.

As the kneecap slips out of the joint or as it slips back in, it often strikes the end of the femur. This may result in a piece of either the patella or the femur’s joint surface being knocked off. The resultant fragment may be just a piece of cartilage or a piece of bone with its overlying cartilage. Additionally, it may remain partially attached to its usual site or become loose within the joint.

Patella

Patellar Instability – Causes

Patellar instability frequently occurs from one of two mechanisms. The patella may be:

- Pushed. The patella is struck on its inner border by a force directed towards the outer aspect of the knee away from the opposite leg.

- Pulled. A twisting injury with the foot planted while the knee is rotated inward causes forces around the knee to “pull” the patella out of the joint.

These injuries often occur while pivoting or cutting during sports but they may also occur during a fall or while stumbling.

There are a number of factors that can increase the risk of a patellar instability injury. These are:

- Weak knee muscles (Quadriceps)

- Flat trochlear groove (Trochlear Dysplasia)

- Anatomical variations in position, shape or rotation of the bones of the hip, thighbone, knee or leg

- Double jointed

- Female sex

- Young age (<30 years)

- Athletic activities